From Salvage to Showroom

Shine—Bringing Paint Back From the Dead

CAR

CARE

BY RIK

PAUL |

From

Salvage to Showroom Shine—Bringing Paint Back From

the Dead

Pro Detailing Tips

The Latest Moves

in Detection Tech

The Ups & Downs of Tire

Pressures

New & Notable

FYI

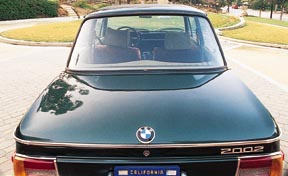

| It began with a phone

call. A friend had just bought a bargain-basement-priced

’76 BMW 2002. Although it was mechanically in good

shape, the paint job was trashed. It was badly oxidized

on the hood, trunk, and roof—with a chalky pallor and no

reflectivity left at all. Plus, the hood had deep

scratches that looked as if someone had done a break

dance on it wearing a suit of 60-grit sandpaper. Wanting

to boost the car’s curb appeal without having to resort

to the hassle and expense of repainting, my friend’s

plan was to see how much life he could breathe back into

the paint through tried-and-true finessing techniques.

With camera in tow, I followed his progress.

While this was an extreme example of deteriorated

paint, the scenario is common, even for vehicles only a

few years old. Exposure to sun and the elements starts

working on a vehicle’s paint the day it rolls off the

assembly line. Oxidation can leave it looking dull and

lifeless; acid rain, bird droppings, and other

environmental debris can produce etching and stains; and

day-to-day use can cause light scratches. All this can

make an uncared-for finish look old well before its

time—and shave hundreds of dollars off the vehicle

resale value.

The paint on the 2002 was not a factory finish; it

had been repainted (without a clear coat) and,

fortunately, none of the scratches had gone beyond the

outer coat. This is important; as long as defects don’t

go completely through the outer layer—whether clear or

color coat—they can often be finessed out. Which means

removing enough of the paint layer to take out the

defects and return the surface to a smooth, glossy

finish. This, in turn, requires the use of abrasive

cleaning compounds and, in more serious cases, wet

sanding. With the BMW, the owner—Rich LaBrie—decided to

use Meguiar’s professional line of Mirror Glaze

products, which includes cleaners of various abrasive

levels and the company’s Unigrit sandpaper, made

specifically for use on automotive finishes.

Out With the

Old...

While most light

defects can be removed with a good cleaner or rubbing

compound, for more serious problems, such as heavy

oxidation, deep scratches, or orange peel, wet sanding

is a faster method of removing paint. The typical way to

sand a finish is to begin with the least abrasive paper,

then if that’s not enough to remove the defect, move up

to increasingly more abrasive grades. Coarser papers,

however, leave behind a rougher surface, which then has

to be smoothed out with sequentially finer grades. Since

the 2002 was in such bad shape, LaBrie started with

600-grit paper to remove the dead first layer of paint

and work out the deeper scratches. Once that was

accomplished, he moved to increasingly finer paper

(1000- and 2000-grit) to smooth out the relative

roughness left by the initial grade.

Sanding an automotive finish isn’t for everyone. You

have to be careful not to remove too much paint, which

is especially easy to do around contours or corners in

the sheetmetal. 1000-grit or heavier is particularly apt

to remove paint quickly. Beginners should stick with

2000- or 1500-grit paper until they get a good feel for

the process. Unless you’re working on a very small area,

it’s advisable to wrap the paper around a sanding block,

which will elicit an even result; finger pressure alone

can create subtle waviness in the paint surface.

Wet sanding helps the paper last longer and generally

provides better results. To do this, halfway fill a

clean bucket with water and soak the paper in this prior

to use. In addition, it’s a good idea to keep a hose

nearby to wet the area to be sanded and allow the water

to flow over the working surface as you sand. Rinse the

paper frequently to avoid any buildup of paint particles

that can cause new, deeper scratches. As you sand, check

the surface regularly to see how the removal of the

defect is progressing; don’t remove any more paint than

necessary.

By the end of the wet sanding, the 2002 already

showed a dramatic improvement. The rough 600-grit paper

had done most of the work, taking off the heavy

oxidation and enough paint to eliminate most of the

scratches. Then, the coarseness left by the 600 was

worked out with the fine 1000- and ultrafine 2000-grit

papers, leaving only light sanding marks.

...In With the

New

Next, it was time

to move to the cleaners and polishes to bring back a

like-new shine. Mirror Glaze cleaners are available in

three levels of abrasiveness: heavy-, medium-, and

fine-cut. On most finishes, with light defects that

don’t require sanding, you can begin the finessing

process with one of these cleaners. As with the

sandpaper, it’s recommended to start with the least

abrasive product possible that will do the job. Locate

the worst area of the finish and choose a small section

(about 2x2 inches) to use as a test. First, go over it

with a light abrasive product and see if it’s successful

in removing the defects and smoothing the surface. If a

little more abrasive is needed, choose another product

and go over the same area with it. When you find which

level of abrasive works best, you can use that product

for similar areas, or move back to a lighter product for

areas with fewer problems. Next, it was time

to move to the cleaners and polishes to bring back a

like-new shine. Mirror Glaze cleaners are available in

three levels of abrasiveness: heavy-, medium-, and

fine-cut. On most finishes, with light defects that

don’t require sanding, you can begin the finessing

process with one of these cleaners. As with the

sandpaper, it’s recommended to start with the least

abrasive product possible that will do the job. Locate

the worst area of the finish and choose a small section

(about 2x2 inches) to use as a test. First, go over it

with a light abrasive product and see if it’s successful

in removing the defects and smoothing the surface. If a

little more abrasive is needed, choose another product

and go over the same area with it. When you find which

level of abrasive works best, you can use that product

for similar areas, or move back to a lighter product for

areas with fewer problems.

| To take out the

light sanding scratches left by the 2000-grit paper,

LaBrie chose the Heavy-Cut Cleaner. A nice advantage of

Meguiar’s cleaners is that they use “diminishing

abrasives,” which gradually become less abrasive as

they’re worked. This means that even the abrasives in

the heavy-cut cleaner gradually wear down to work as a

fine polish that leaves a smooth, glass-like surface.

The diminishing abrasives also permitted LaBrie to

move directly from the heavy-cut cleaner to an ultrafine

swirl remover to take out any haze or swirl marks left

from the cleaning and bring out a high, reflective

gloss. At this stage, he also was able to use an orbital

buffer to speed up the process and reduce the elbow

grease needed for the remaining steps.

The swirl remover produced a brilliant, glistening

finish that left onlookers following the project

awestruck by the transformation. For a final polishing

step, LaBrie opted to apply a coat of Showcar Glaze to

further nourish the paint and enhance the gloss, and

then Meguiar’s’ Medallion For All Paint protectant to

help protect the paint from environmental damage. When

the project was finally complete, the 2002 looked like a

newly painted car with dramatically higher curb appeal,

which would probably draw a much higher price during a

resale. Meanwhile, LaBrie’s total outlay was about $100.

Overall, it was a good lesson for owners of cars with

worn paint: There may be life in that dead finish after

all.

|